The 9am Train to Paddington – not empty, no corridors

Sunday 7 January 2024

For the kids’ first away game, we went big. The FA Cup provided the chance of a glamour tie, the third round draw taking place before Christmas, with fixtures played in early January. Historically, FA Cup matches are cheaper, and the away allocation is bigger. There are reasons, but they are pretty dull.

We waited for the 3rd round draw in a state of breathless excitement. This time last year we went on a run, of sorts, culminating in pulling Man City out of the hat. We had the radio on during bath-time and everybody screamed when it happened; then Elliot cried, overwhelmingly excited by the prospect of seeing Man City, and overwhelmingly sad that Bristol City would now not win the FA Cup, and whilst I said we might, to which Penny replied, jauntily, “That’s the magic of the FA cup!” I admired her realism, her pragmatism, and knew that our run would end. The chances of it not ending were exceedingly slim. But stranger things had happened; mythical encounters; last time we played in the semi-final of the EFL cup in 2018, it was close; 5-3 on aggregate over two legs, the teams separated by a moment of controversy – and probably men like Agüero, De Bruyne, Sané. That was then, this is now. By way of commemoration, The 3 Lions welcomes the City team with a huge banner. It sits beneath a ‘lest we forget’ frieze, images of brave soldiers, and reads: “Bristol City vs The Cheats”. If that wasn’t clear, it also says “Welcome to Bristol, you cheating cunts”.

We walked along North Street, Elliot wide-eyed at the noise, the feeling in the air, emotions carried on by each person heading to the ground, a widening aura of palpable excitement. A crowd clumped together outside El Rincon, a small tapas bar which has a nifty side-line as a City pub on match days, chants and pyro blasting outwards. We made our way in and the concourse was full, reeling, noisy. We walked words the South Stand, but it was blocked by a chanting mass, boys on shoulders, flags and scarves waving. It was thrilling, unique stuff, right up until the moment Phil Foden put the ball in the net with ridiculous, insouciant ease after 6 minutes. By the time Kevin De Bruyne, the actual Kevin De Bruyne, the most lavishly gifted and incisive Belgian since Hercule Poirot, stepped this way then that before caressing the ball into the net from fully thirty yards out, we were aware that this is what we expected and we walked home sad but sated by proximity to the power of petrochemical millions and opportunity to see the finest players in the world walk onto a rectangle of grass in BS3.

The following year, we pulled West Ham out of the hat. They are no Man City. Not too long ago they were here with us, in perpetual championship limbo. Despite their heritage, and Bobby Moore, they are something of a yo yo. We are excited to be playing premier opposition, but I tell the kids we won’t be going. It’s in February and it’s a long way and it will be too much, but if we get a replay we will go to that instead. They understand, I think. Secretly I get tickets, because it doesn’t look that difficult, GWR on a Sunday morning out of Temple Meads, there can’t be that many on that train, then the shiny new Elizabeth Line to Stratford and a short walk. Belle thinks it could work, and I invite her along. She says “yes but not for the football, I’ll go to a gallery on my own thank you.” We book lunch at Stratford for 12.20 and everything is perfect. I mock up a ticket for the kids for Christmas and when they open their gift, in a cannily forged West Ham envelope with club crest and everything, there is an all-time shitting of the bed. I THOUGHT WE WEREN’T GOING! YOU SAID! and like all good dads I point out that at no point did I say we weren’t going , I just told them it had sold out, which it had. Penny cries in shock and amazement.

I have always liked trains, but the experience has changed. If I could find and show my youthful self that the safest of places, the most joyful of middle age experiences, is taking the train with a Sunday newspaper and a pack up, completing the cryptic crossword whilst the green hills roll past the window, I would have been surprised. In reality the railways are utterly shit and hideously expensive, another symptom of broken, privatised Britain. I have written about trains before, the journey, the space in time, heading to Penzance to start a 900 mile bike ride. That train journey was bucolic, perfect, the sea filling the windows along the South Devon coast. Maybe it was one of the things which prompted my local book shop to describe me as ‘the Phillip Larkin of cycling writing’, because he loved a train journey too. That’s about all we have in common. Oh, he liked bicycles, and visiting churches in a secular capacity and wondering (and wandering) about time and meaning. But the train features most; the opening poem in The Whitsun Weddings is a swooping movement into Hull from the heavy hinterland of the Humber as it wallows towards the North Sea, then back out towards ‘unfenced existence’. Later, he uses the journey from Hull to London as a was of creating space and time, to observe, reflect, feel things. In the title poem of The Whitsun Weddings, he sees newly-wedded couples, watches them embark at a series of stops, heading on honeymoon on the same time, because of the anachronism of the Whitsun tax break for marriage. He is in time, yet outside of it, a part of the circus, but removed from it. He does not mention football, but covers ‘someone running up to bowl’, A glimpse of sport from the window of the train above the landscape. Mostly we wrote about people, potential, and mortality. I’m sure I can apply these to Bristol City.

Louis MacNeice loved a train journey too. For him, the silence of late night train travel, with the stars forming ‘intolerably bright holes punched in the sky’ became a silent reverie about time and mortality, our place in the universe. He remembers being a child, running from side to side across the carriage, marvelling at the sense of time, of ‘how very far off they were’, a joy tempered by the realisation that the light leaving each star, 40 odd years ago, may never arrive, and it if does, there will not be “anyone left alive” to admire it. When I read this poem I can see and feel the inky blackness of time and space through the window, the blanketing force of time, the comfort and terror of the stars, which may or may not even be there, just a shadow of light. It is a feeling I lean into, but also am afraid of, and one i go to football matches to forget, because I can live in the moment, instead of being paralysed by the moment.

We wait for the 9am on Sunday, 7 January, and the feeling is of a frail, travelling coincidence. The Whitsun crowd has been replaced by a different force, similarly hedonistic, but not anxious, not chewing a lip in fear of the future, but embracing the possibilities the day might bring. A crowd – an enormous crowd – far far bigger than I anticipated because I am stupid and what did I think was going to happen with tickets costing a tenner and 9000 seats available – waits on platform 9 for the departing trains to London. There is no-one else at the station, only a couple of thousand Bristol City fans, preparing for their big day out. Preparing means carrying at least 16 cans of Thatchers Gold for every man, woman and child on the train. Until you have stepped foot on a football special you have no idea. The train shakes with noise and fervour and drunkenness. It is a no-place, it is an airport, insofar as you must drink, and time does not matter, only the fact that this is an away day, and it is not a train, but a rolling football crowd.

The train somehow becomes Macneice’s journey, time expands, dilates, by the time we reach London there will be no-one left to marvel at the passing of time, we fell into dark matter, somewhere near Westbury, where he train stopped, for over an hour. Then it started, but it went backwards. We would listen to the announcements but the noise, the singing, the singing about Bristol City, but primarily about the Gas, and there are no longer any swears left for my children to hear, the singing drowns out the plaintive apologies for a conductor who sounds full of regret that she opted to take this shift, the shift when 3000 Bristol City fans decided it was time for a big day out.

Ultimately things remain just about the right side of civilised, and it is a technological and social leap forwards from the days of the football specials. I have heard about them, “it gives us the chance to isolate the fans from other passengers”, even the reviled bubble matches. It seems anathema to me, both in my previous incarnation as a sporadic home-only fan,and as a season ticket holder with kids. I don’t think too much about the past, the way football has changed, I embrace the sense of safety. I don’t have fond memories of this kind of thing. I remember bottles flying across the road junction at Sidwell Street in Exeter, as the Hull fans came charging across. I have never seen my friend remove his club colours so quickly. I’m baffled by it, two sets of fans, identical in almost all aspects: a love of football, a passionate sense of place, identical outfits. identical demographic, market segment, working patterns, leisure choices, united in the sense that each is the sworn enemy. Of course I understand the deeper sense of malaise and nebulous anger, the calculated indifference and neglect from a government that believes levelling up means directing millions of pounds towards Tory marginal seats, but I’m depressed by the continued failure of people to see precisely where the enemy lies. The good old days, loved of men of a certain age, consist of desperately uncomfortable stands, callous police indifference, catastrophic stadium safety, violence, crushes, fires and death. A stadium fit for families, for women and children and men who don’t prioritise violence? I’ll take it thanks.

The train has been cancelled. It is then reinstated, it no longer has 8 carriages, but 4. There are over a thousand people on this platform. Between them they have 6 cans of Thatchers gold each, with the exception of the family of four in the middle, who have the Observer and some chocolate corn cakes. We have no seats, no-one has any seats, the rules have changed, and everyone vapes and drinks and every now and then a chant rips up and down the carriage. The toilets, oh the toilets. We can get to them, through much effort, care, awkwardness. But the end result is a horrifying medieval tableaux, ankle deep in piss. On my return to my seat I take some photos; a group of men have tiny zamubccas in a box and it is 9.47am, so I take a photo, and one of them says

Why you taking a photo bruv

With an air of menace. I try to explain, oh it’s a record of the day, you know, colour, blah blah and I have never, ever felt so middle-aged and middle class. I walk away, back to the middle of the aisle where I am crammed against everyone else and my children are sort of enjoying the madness.

And we are unloosed, somewhere becoming rain. Through Paddington station, where everyone, literally, everyone stops and stares, because of the noise and the chants. The whole of Bristol has come to London for a big day out, rolling through the station on a wave of noise, to the untrained ear, the sound of violence, or aggression. It dissipates as people move away, use the toilet, head to the tube, get on the Elizabeth Line. There is still a wash of red and white colour and noise, through the long rectangular snake of the carriages, enough to unsettle and attract confused looks. Who are these people? Why are they here?

Our plans are amended on the hoof; the train has robbed us of time, two hours to be precise, leaving about 45 minutes to get to the London Stadium before kick off. It’s a really long walk from Stratford Station, especially for away fans, directed out towards the edge of nowhere along a relief road, through an industrial estate, before looping back around over a bridge towards the back of the stadium. We make it with some time to spare and take our place amongst the nearly 10,000 other Bristol City fans in a stadium built for 68,000. It is cavernous and impressive in so many ways, but none of these ways relate to its current incarnation as a venue for watching football. We are a long way from the pitch, beyond strange voids in the seating and past a running track which sits underneath the stands. It was a financial decision, to come here, to increase match-day revenue and to allow the government to avoid another white elephant. But it smacks of desperation, and speaks of money over community, shifting a club three miles up the road. I can’t imagine what is like to come here, week after week, to sit in this draughty mega bowl and squint down to try and work out who has the ball, whilst machines pump out pitiful amounts of bubbles. They sold their soul in a metaphor for the gentrification of football, of East London, and of history and memory. There are 62,500 people here and it feels hollow.

It takes approximately 4 minutes and 40 seconds for things to turn to shit, whereupon Pablo Fornals lofts a ball over the top for the extraordinarily rapid Jarrod Bowen to bring it down with skilful insouciance, avoid Max O’ Leary and poke it into the net. It is incisive and devastating. We fear a massacre. This is how it works. Money and quality wins out, usually with ruthless efficiency. There is a brief silence amongst the 9,000 of us, 3km from the pitch, then a slow and steady roar, renewed chanting, exhortation, as the team slowly make their way back for kick off. My kids are angry, Penny especially so. She feels the football so hard; defining elation and despair. She feels everything, she is amazing, an open book of feeling. It terrifies me; I see myself, the patterns of my mind, my over-sensitivity, constant thinking, layers of questions, peaks and troughs. Elliot is standing on the chair, because everyone is standing, because that happens at away games, everyone stands, and they refuse to sit down, even when politely asked by hi vizzed stewards.

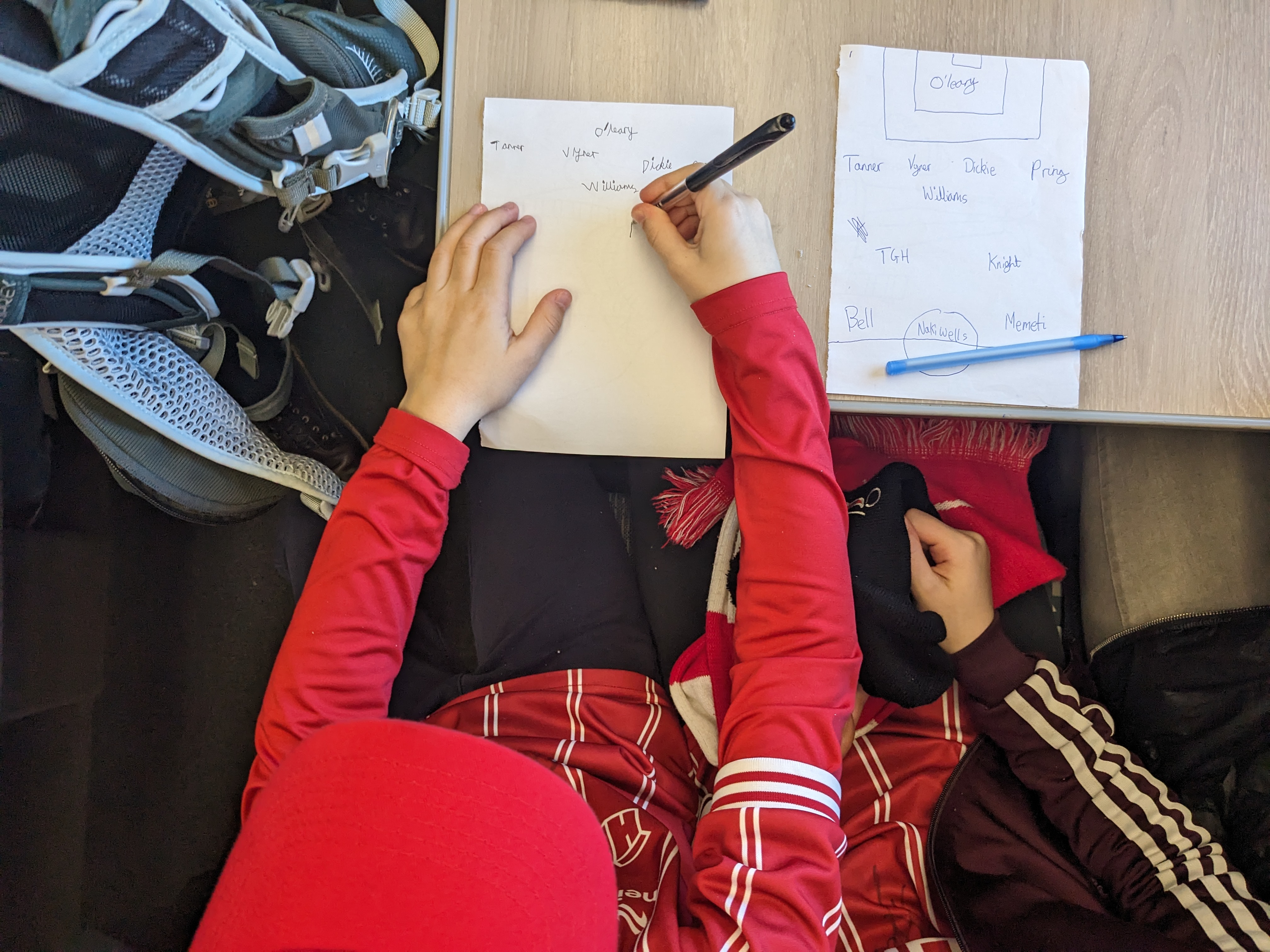

We settle in, try and maintain hope. City claw back into the game, inch by inch, fan favourites Cam Pring, Joe Williams, Jason Knight, maraud and attack, go hard. We make it to half-time, only the goal down. The game is not done. It’s never done, even when you think it’s done. The players have ‘always believe’ on the back of their shirts, below the neck, and we have to believe, otherwise why are we here? What is the point? Who even are we? It’s a truism, always, a cliche, but it’s compelling. We watch the half-time stuff, it’s utterly alien. References to people and places we really couldn’t give a shit about. Someone died, a lifelong fan. That’s sad. There’s some kind of kicking contest, hit the ball in from the halfway line, or hit the crossbar, I can’t remember, although I remember someone hoofing it and missing and it was funny. It’s like being at a wedding, but not knowing anything about the people, hearing the stories, the bonhomie, watching the video clips, laughing in the right places.

The teams come out, City are playing towards us. It’s the way in the second half. There is a general understanding at all grounds that the away team attacks towards the away end in the second half. There is a coin toss, but it confirms the expectation. Occasionally a visiting team seeks to disrupt these, they switch round. It’s gamesmanship, and it sucks and it gets roundly booed but no-one really cares, it’s just one of those things that just happens. Some other of those things that just happen include: a player that used to play for you but now plays for them who you liked comes towards the away end to take a corner and gets a polite ripple of applause, before responding with a short clap of his own, then gets booed, gently, and we laugh, and the game carries on. A player that used to play for you but now plays for them who you didn’t like or who left under a cloud comes towards the away end to take a corner and gets roundly booed and called a wanker repeatedly and typically responds with a theatrical bow or some other minor gesture designed to ignore or even inflame but only slightly. The away fans sing ‘do do do football in a library’ and then ‘shhhhh’ because they are singing all the time and can’t hear the home fans even though the home fans are singing.

In the 61st minute, everything changes in a moment of sublimity. The ball goes to Jason Knight; (Jason Knight Knight Knight) who passes it straight back to Joe Williams who imparts alchemy, channels something else, some sorcery, through his right leg, striking down onto the ball, a skidding, scuddy movement that spins the ball into the ground and forwards to Tommy Conway, (the crowd moves, suddenly, as one, stiffens, makes an involuntary noise, collectively, roars a bit, something like that) who takes it on the outside of the foot, (the noise pitches up, the moment, time and everything else, everything, stops for this moment), flicks it forward, runs forward, sets himself at speed with a shimmy of the legs (the crowd noise holds, it’s not even a noise, an involuntary spasm of sound), then wraps his right foot around it and places it across the goalie in the bottom left corner – it’s so precise, it is one chance, it requires technical accuracy, momentary adjustment, everything, and Tommy Conway does these things.

It has taken five seconds for the ball to move from Joe WIlliams on the half-way line, to the back of the net, via Conway’s right foot. In that five seconds, the crowd has changed from subdued, tense murmur, to sudden, primeval elation, as one. It is limbs, it is a meme of limbs, it is a scene that will be replayed again and again, the shaking movement of limbs amongst 9000 people at once. We are a part of the limbs, we are screaming, we have no control over the sound or movement, we just respond. It is instinctive, emotional, intense.

It is the highest point of the away game, the best moment for many fans since Korey Smith scored the winner against Man Utd in the cup in 2017. For a mid-table championship club, these are the only moments we have; there is no trophy winning moment, no prolonged parade, no march to glory, there is only the brief flash of joy in the unexpected. It is everything.

Leave a comment